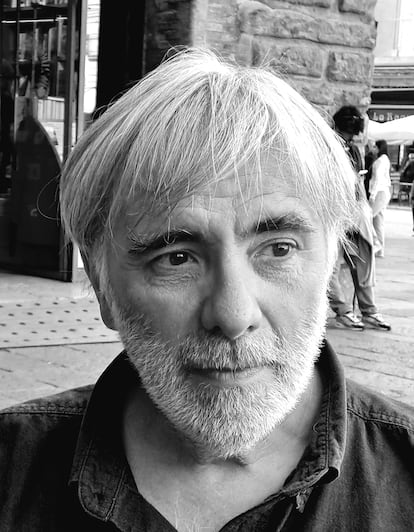

Sergio Ruzzier, the writer “too strange” for some editors but adored by his young readers

Time passed, but the page remained blank. “Let's see if you write something,” the teacher snapped. She had given the class three options to choose from, and even added a fourth: free writing. Still, the boy wasn't making any progress. “He was a bit unlucky,” admits Sergio Ruzzier, who was nine at the time. That day, to make matters worse, he says he was “especially slow.” Until he had an idea: “Can I make a comic?” In a school in the mid-seventies—and probably today—no one was a given. Except for Mrs. Santarelli: “If you do it seriously.”

The illustrator and children's author, now published and acclaimed around the world, still considers it "a pivotal moment" in his life. So much so that he still adores his former teacher and remembers what class he was taking when it happened, the day of the week—it was a Thursday—and the story he concocted: a toothache forced Dracula to go to the city in search of a dentist on a Sunday, when everything was closed. "It was the first time the adult world supported my interest," he celebrates. "I don't think I've changed much since then, either."

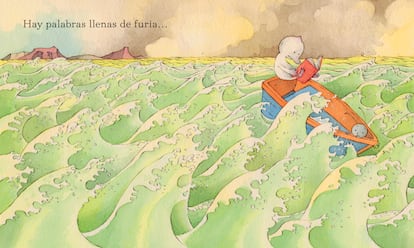

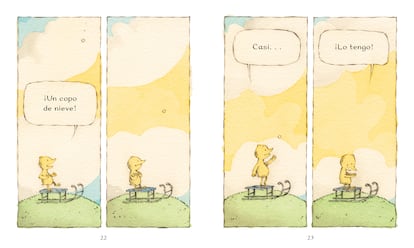

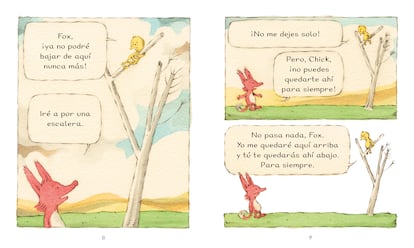

The truth is that he continues to draw and have strange ideas. Even too strange, for some publishers. The audience that counts most, however, supports him: Fox & Chick (Liana) is one of the most acclaimed children's series by both children and critics; Two Mice (A Buen Paso), What a Silly Book , or the upcoming Spanish-language publication of The True Story and No, Said Custard the Squirrel (all in Liana) expand a picture with touches of humor, rebellion, tenderness, friendship, and creative freedom. Unique, perhaps. Peculiar, certainly. Like the fact that a man from a metropolis (he was born in Milan and lived for many years in New York) has moved to a mountain village with more feline than human inhabitants: four permanent residents and eight cats. Or like the fact that the first sentence of Ruzzier's biography for the Italian publisher Topipittori highlights that as a child he played "who dies best."

―What was that?

"I grew up in Lorenteggio, on the outskirts of Milan. There were fields all around; it was a group of six houses, surrounded by a garden. And about twenty of us children played together. We'd all line up, and one of us would pretend to shoot or throw arrows. Whoever died in the most spectacular way would get the upper hand, eventually becoming the next in charge."

To understand Ruzzier, it's also helpful to look at his most famous characters . Fox is a responsible, patient, and sensible fox. Chick is a chaotic, naive, curious, almost uncontrollable little bird. The dynamic between the two is reminiscent of Calvin and Hobbes , though less biting: the little boy follows his anarchic impulses; his furry friend tries to steer him back toward balance. It happens in each book, of three stories. And, constantly, in the author's head. “I'm both. My rational side wants things to go a certain way. But the other, disruptive side throws the plans out of whack. In the end, it works better because there are both of them. There were reviews of the first volume that said, ' Chick was too unbearable and Fox too patient .' To respond, I rewrote it so that everything worked perfectly. It turned out to be deadly boring.”

The Italian has had to defend his work more than once. “I often have to fight, especially in the United States,” he summarizes. “I refuse to submit to moralistic, useless rules; they’re afraid of negative reactions. It’s ridiculous. In a recent book, I had to draw a kitten and a mouse, who were actually two girls, making tea. And the editor was very worried that it would be obvious they weren’t making it for real, because they might burn themselves.” Another work he recently proposed was said to be “on the strange side” of his career. In general, there’s a label that dogged him early in his career and occasionally returns: “ Too quirky .” Too eccentric. Ultimately, it happens to him from behind the desks. But a Mrs. Santarelli doesn’t always appear.

“My mind is still similar to that time. I still have a certain inner distaste for the adult world, for its falsehoods and moralisms. I don't deny that I'm an adult too; obviously, I don't want to be a Peter Pan. Unfortunately, I live in that world. But I'd rather be Pippi Longstocking,” he notes. He was a teenager when he began to understand that drawing was something he was good at, that perhaps it could be his profession. He didn't read many novels, but he did read Asterix, Lucky Luke, Pon Pon, Pinky, the Peanuts, Mickey Mouse, and Tex Willer. And, later, Crazy Kat, Popeye, and Dick Tracy. The lazy student, prone to procrastination, changed when faced with cartoons: he studied them thoroughly, their structure, the lines. He began with adult strips, melancholic, somewhat violent, “pessimistic,” as he defines them. In the late 1990s, already in the US, he tried his hand at children's literature. And to this day, to the delight of thousands of children.

“I don't think the artist has a responsibility as such. What I do feel is the need, the obligation, to do the best work I can,” Ruzzier adds. He also confesses that his resume includes works he's fully satisfied with and others he's much less satisfied with. So he always tries to push himself a little further: “If you've finished the drawing and you know how to do it better, you should try again. It can be important.” These are the words of the boy who didn't want to make an effort. Teacher Santarelli would be proud.

EL PAÍS